Trade Dress Protection under Fair Trade Act

published on 6 May 2016

A product’s appearance or shape is a key factor for successful marketing in many occasions. By designing a fanciful, creative, or aesthetic appearance, the product can more easily attract the consumers’ attention. While manufacturers often invest in developing product designs, how the appearance is protected from third party’s misappropriation, piracy, or plagiarism is a major issue. In Taiwan, the appearance of a product can be subject to IP protection such as design patent, trademark, copyright, or, specifically, trade dress under the Fair Trade Act. Unfortunately, as the Taiwan Intellectual Property Office interpreted, a trade dress can be protected as a three-dimensional trademark only when it has acquired secondary meaning among relevant consumers after a long-term use in the market. Besides, design patent is way more than a walk-in matter. A design must possess creativeness and novelty in order to be patented. Such standards would be hard to achieve for some commercial products having unique but commonly seen elements. These products may gain rapid popularity among consumers but the IP protection thereof is always insufficient and left behind. In other word, expecting an immediate trademark or design patent protection for an instant-hit newly released product is usually difficult.

In order to close the loophole, Article 22 and 25 of the Fair Trade Act respectively prescribes “prohibition of use of representation of goods” (Article 22) and “prohibition of deceptive or obviously unfair conduct compromising trading order” (Article 25) as legal instruments for trade dress owners to safeguard their IPs. Details are as follows.

Article 22: Protectibility of Representation of goods

Referring to a product’s featured distinctiveness or secondary meaning, the representation of goods serves to indicate the origin of products so as to enable an individual to identify the authentic source from the other. By statutory definition, a representation can be a person’s name, a business or corporate name, a trademark, a container, a package, or a trade dress of goods demonstrating a given product, etc.

Generally, a protectable representation of goods shall be well-known that relevant consumers may recognize where a given product is from when it is used on the goods or services. For determining the level of fame, a court has the discretion to evaluate several factors including the volumes of commercial advertisements, duration of marketing, sales numbers, coverage on media, reputation and quality, market share, and surveys in relations to the product. On the other hand, when considering similarity between an allegedly infringing and an authentic product on which a representation is used, the court will not be restricted to the list of classification of goods under the Trademark Act. For instance, a beer coaster can be infringing a liquor bottle by using latter’s well-known trade dress even though two products are classified in two different categories.

To trigger Article 22, the infringing product must also have to cause confusion to relevant consumers as to the authentic source of goods. Three principles are available to determine confusing similarity. The principle of observation-in-whole requires comprehensive comparison of the two disputed products with their general features leaving along the details. The principle of main-feature-comparison, instead, focuses on the difference of particularly significant features. Last, the principle of isolation-observation provides a view from the perspective of a consumer whether confusion occurs when the two disputed products are seen in different time and places.

Article 25: Dead Copy as a Deceptive or Obviously Unfair Conduct

In cases where the degree of fame of a product’s appearance does not reach the level required by Article 22, it may still be protectable under Article 25 by asserting infringer’s conduct of substantial copying as a type of unfair competition. In practice, to determine the ground of Article 25, the court will analyze whether the trade dress owner’s economic interest is misappropriated by the infringer, whether there is a likelihood of confusion, the mens rea of the misappropriation, whether the plagiarism is completely identical or extremely similar, the relationship and causation between the infringer’s competitive advantage ever gained and the effort for achieving said advantage he/she ever invested, the uniqueness and market share of the plagiarized appearance in the market, etc.

Remedy

Remedies are available as both administrative complaints and civil litigations. Although violation of Article 22 will no longer be subject to administrative penalties, a trade dress owner may still file complaints to FTC against obviously unfair conducts such as dead copy under Article 25. In addition to administrative route, the trade dress owner may straightly initiate a civil action at the IP court under the grounds of either Article 22 or 25 violation.

At the court, a trade dress owner may claim for injunctions or monetary damages. Even though the damage is calculable from commercial gains of the infringer, practically the difficulty during the course of evidence collection may be an obstacle to attaining a reasonable amount, different from the Trademark Act where a statutory multiplier of 1,500 timing the unit price of a infringing product is available for determining a recoverable figure. Given that, for bad-faith infringement, the court may award punitive damages in triple at most.

Case Example: Suntory v. General Biotech Alcohol

Source from: Apple Daily News, Taiwan

Suntory sued defendant at the IP court for infringement on its whiskey bottle appearance and packaging, after its complaint filed to Fair Trade Commission (FTC) was dismissed. The questions in the case are summarized as follows,

- Whether the design of Suntory’s whiskey bottle is a protectable representation/trade dress?

- Whether there is other alcoholic product adopting similar design that dilutes the distinctiveness, if any, of Suntory’s whiskey bottle?

- Whether the brand name and manufacturer’s name labeled on the allegedly infringing package prevents consumers from being misled or confused?

The court found that, viewing the evidence from commercial advertisements and Suntory’s website, Suntory had long been emphasizing the aesthetic features of their bottles. Suntory’s market research evidence also demonstrated the fame of its products by receiving recognition from more than 60% survey respondees. Considering the fact that Suntory’s bottle design is quite unique, the court confirmed its distinctiveness. As for defendant’s counter argument of dilution, the court disagreed and explained that the obvious difference between the two bottles and packages successfully avoided Suntory’s distinctiveness from being diluted. Next, defendant’s argument of no confusion that the brand name and manufacturer’s name are different was neither admissible. The court applied the principle of observation-in-whole to compare the colorations and geometrical proportions. The court found substantive similarity between Suntory’s and defendant’s bottles, which would potentially cause confusion in the marketplace. Based on the foregoing, defendant’s bottle design is infringing on Suntory’s trade dress.

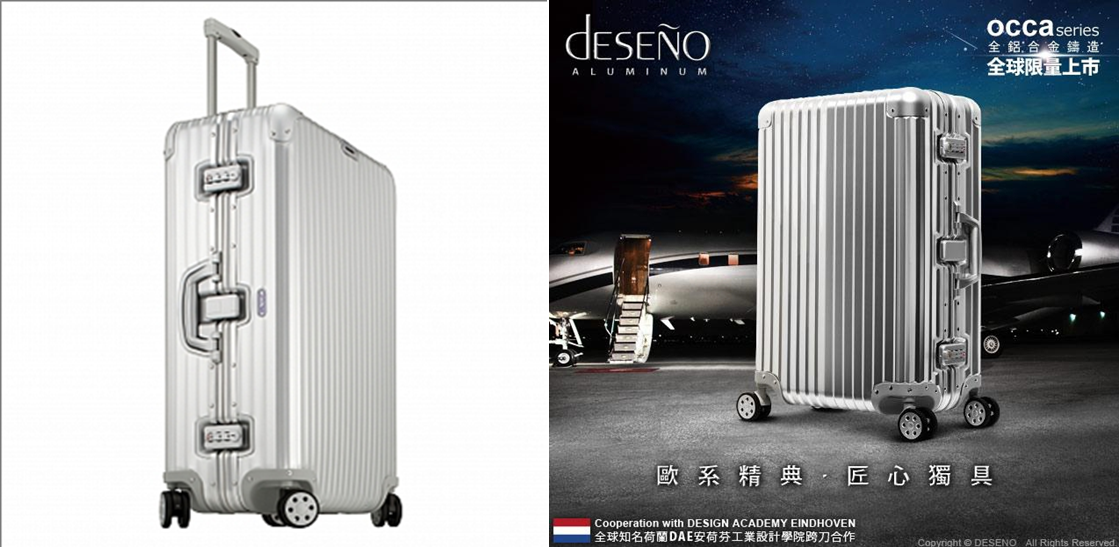

Case Example: Rimowa v. Deseno

Rimowa has been using its signature groove design on series of luggage product lines since 1950, and the same design has also been decorated on its Taiwanese products since 2003. Under Article 22 and 25, Rimowa sued defendant for unfair competition by utterly copying its groove design. The main issue is whether the groove design is distinctive. The court first analyzed Rimowa’s advertisement volume, reputation, and the emphasis of groove features disclosed on the advertisement and webpages, and found that Rimowa’s groove design deserves as a protectable trade dress. As for defendant’s counter argument of dilution that many imported products bearing the same or similar design exist everywhere, the court disagreed by pointing out that those imported products were not as pervasive as they are now until one or two years ago. By applying the principle of observation-in-whole, the court found the two products being confusingly similar and would therefore mislead consumers. Since Rimowa’s groove design is a well-known trade dress, defendant’s use of the same design on luggage is accountable as an unfair competition. The case has significant meaning as being one of few cases where the court recognizes the appearance of a plaintiff’s product as a trade dress.

Conclusion

According to the foregoing, it is understandable that to enjoy a protection under Fair Trade Act for an appearance of a product in Taiwan may not be as easy as wished. The plaintiff would need to present considerable amount of supportive evidence for establishing well-known status and distinctiveness. Since the court is vested with discretion determining relevant facts, success of a representation being confirmed distinctive is not guaranteed. Hence, legal instruments such as trademark and design patent would nevertheless serve as a strategic insurance to secure an even more comprehensive scope of protection. For instance, sending a cease-and-desist letter along with trademark and patent certificates as manifestations of rights would less likely be ignored by an allegedly infringing party.

On the other hand, for the sake of potential litigation in the future, the marketing or sales staff should frequently promote the uniqueness of product’s appearance in the course of advertising. Only in this way may the court be more likely to confirm the distinctiveness of a trade dress. Lastly, as a trade dress is growing famous in the marketplace, swift and timely legal actions against any fake or infringing products is necessary to defend dilution challenges.