A Market Pioneer in Battery Swapping Networks

Won an Infringement Lawsuit

Gogoro is a Taiwan-based spearheading enterprise for innovative vehicles. Since the rollout of the first model in 2015, Gogoro has established itself as not just a two-wheeled smart scooter manufacturer but also a core developer of a battery swapping platform that strategically partners with many interested electric vehicle companies. With its superior reliability and compatibility, the Gogoro Network has become the most widespread battery swapping infrastructure in Taiwan, used by partnering brands including Aeonmotor, eReady, eMoving, PGO, Yamaha and Hero (India).

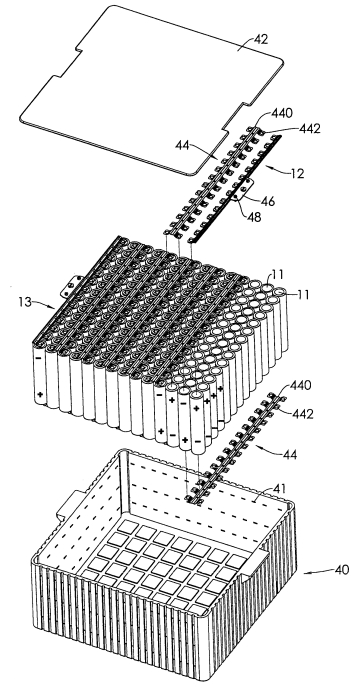

Stone Energy Technology (“Stone Energy”) is another company engaged in the development of novel electrical power storage systems. Stone Energy accused Gogoro of infringing two Taiwan invention patents: I423140 for “anti-counterfeiting battery pack and the authentication system thereof”, and I308406 for “battery pack” (See Fig. 1), alleging that Gogoro had implemented the patented technology in—at the very least—their S Performance model series scooters.

Stone Energy claimed damages amounting to over TWD 350,000,000, or about USD 12,550,000. Gogoro entrusted Tsai, Lee & Chen to defend.

With the decision having been pending for less than 18 months, the IP Court ruled in May 2021 that all of the plaintiff Stone Energy’s pleas would be rejected.

The court started with the conventional claim construction of the two asserted patents. Next, the court analyzed whether each and every element recited in the patent claims term-by-term corresponded to the disassembled parts of the allegedly infringing batteries of Gogoro.

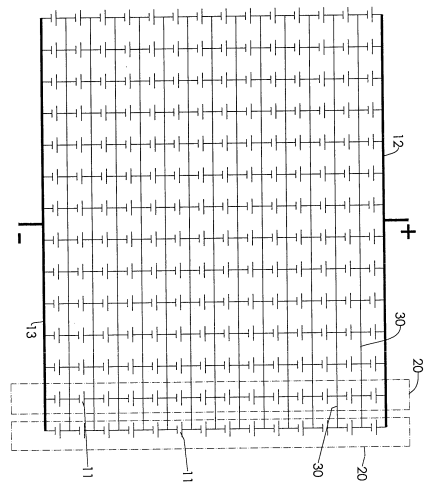

Firstly, for the ‘406 patent, in the several disassembled elements, the court found that at least three such elements in Claim 1 were different from the corresponding ones in the accused product of Gogoro. An example of this was Element 1C, which had multiple cells connected to form “cell strings,” each of which was defined by the court as “multiple cells connected to each other, with one cell’s positive terminal connected to another’s negative terminal in series.”(See Fig. 2) In contrast, the cells in the accused product were not all connected in this precise fashion. More specifically, the positive terminal of one particular cell was connected to another cell’s positive terminal “in parallel.” To give another example, Element 1E required the claimed battery to have a minimal amount of cells arranged in a 4x4 matrix. However, the accused product’s cells were arranged in seven columns, with the number of cells in each column being 5, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6 and 5. The court found this not to be a matrix formation as claimed. For the foregoing reasoning, the accused product was not read on by Claim 1 (or indeed by any of its dependent claims) of the ‘406 patent.

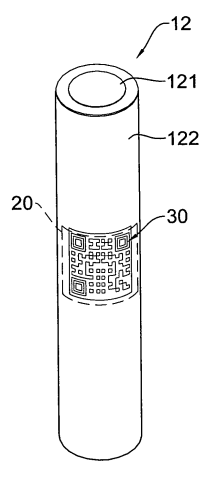

Secondly, for the ‘140 patent, there were likewise several elements in Claim 1 of that patent which were distinguishable from those in the accused product of Gogoro. For example, Element 1E in Claim 1 had “an inside identifier”, securely mounted inside the cell body, in which was stored a first identifier code. (See Fig. 3) However, after disassembling the accused product, it was discovered that there were text and symbols of a darker tone on the protective external layer of the battery cells. It was made clear by the court that these were supposedly an “outside identifier” rather than the “inside identifier” which the plaintiff had erroneously asserted them to be. Furthermore, Element 1F had an outer identifier, “securely attached” to the outside of the protection layer, which stored a second identification code. In the accused product however, it was found that the external model code and the caution notes on the protection layer did not suffer damage when the protection layer was removed from the battery cells, meaning that the outer identifier was not as “securely attached” to the protection layer as was claimed in the ‘140 patent. Besides, the model code NCR18650BE0 was consistently printed on each of the battery cells. It was not possible to distinguish one cell from another, nor could the counterfeits be authenticated from the genuine ones. It cast some doubt over whether the model code NCR18650BE0 qualified as an “identifier” as was stated in Claim 1.

For similar reasons, other claims in the ‘140 patent were not read on.

To briefly conclude, the court did not find that Gogoro’s batteries fell within the scope of Stone Energy’s alleged two patents after the process of construction and element-by-element analysis. Therefore, it was ruled that Stone Energy’s patents had not been infringed. This being the case, the court did not further investigate or review the validity of patents, the damage claims, injunction requests, etc.

Tsai, Lee & Chen successfully defended Gogoro in the trial.

The case is currently on appeal.

On a side note, Taiwan adopts a bifurcated IP system for IP right invalidation and infringement actions; however, the power to determine the validity of a patent claim is also vested in the IP court. In a patent infringement proceeding, a defendant may raise the invalidity of the patent claim in question as a defense. The IP court may exercise their discretion in determining whether the defendant has an effective defense without the need to stay the proceeding for an administrative judgment on the issue of validity. If the court admits the defendant’s defense, the plaintiff loses its infringement claim against the defendant. However, the court’s determination of invalidity is case-specific, meaning that the patent right owner is not prevented from enforcing or asserting its right in other proceedings. In practice, the court does not have an adjudicative order on the infringement and validity of a patent claim; therefore, the question of which should be examined first is addressed on a case-by-case basis. In this case, the court firstly adjudicated infringement before the validity issue was addressed. When infringement was not found, there was no need to examine the defendant’s defense.

Fig. 1: Exploded view of the anatomical structure of the battery pack for the ‘406 patent.

Fig. 2: Illustrative view of how the cells are connected in a circuit in the ‘406 patent. Each of the cell strings (20) consists of cells connectively arranged in series, where one cell’s positive end connects to another’s negative end.

Fig. 3: Perspective view demonstrating the cell (12), cell body (121) and the inside identifier (20) for the ‘140 patent.

Please contact info@tsailee.com for any inquiries.

|